Who is an artist? Musician or machine

A conversation with George Lewis on sound, technology, and creative disruption.

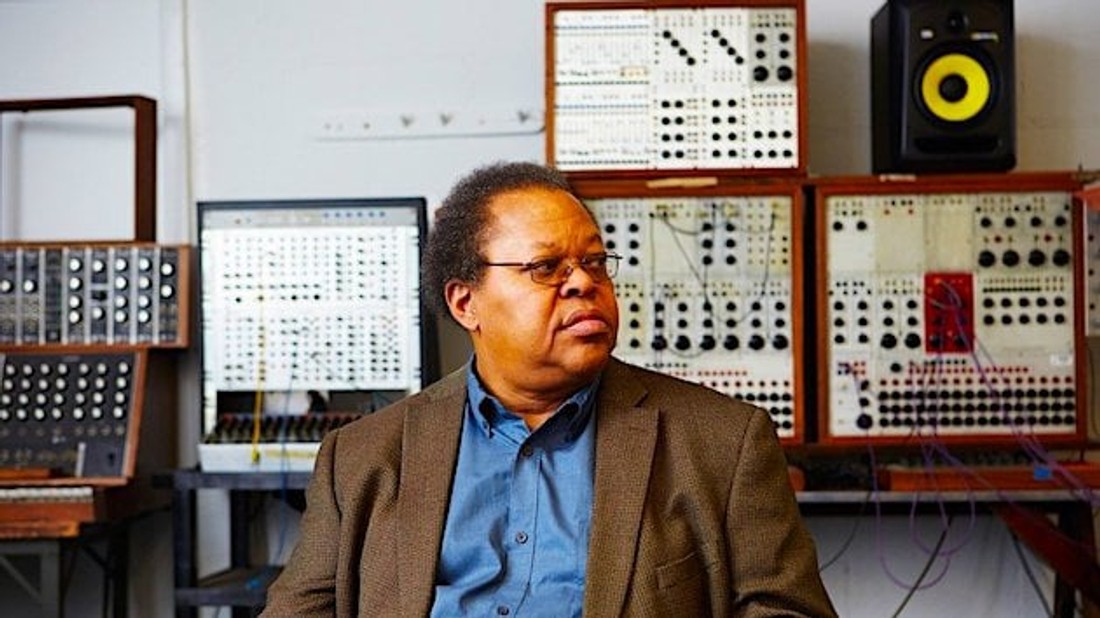

George Lewis doesn’t just compose music — he reimagines who gets to create it. A celebrated composer, improviser, scholar, and professor at Columbia University, Lewis has spent decades breaking boundaries across genres, disciplines, and technologies. One of his most influential works, Voyager, is an interactive music system built in the 1980s that listens and responds to live, human performers.

Now a Fellow at Columbia’s Institute for Ideas and Imagination, Lewis reflects on the future he saw coming and what still needs rethinking in an era where technology is reshaping creativity and authorship.

Question:

Many artists today feel an existential threat from technology and AI — that it might replace human creativity. But you've been collaborating with machines for decades. What is your view?

Answer:

Discussions about AI have changed radically since I began my work in the late 1970s. The people who first inspired me - Roger Schank, and especially Marvin Minsky, who was also a musician - were introspective humanists who used computers to understand “us.” Of course, some researchers didn’t see that the question of who “us” is was central. But most of the popular AI discussions I've read don't seem to care much about this technohumanist project. In fact, people like Timnit Gebru have criticized the anti-humanist and eugenicist direction that corporate AI has taken.

Human creativity can’t be replaced, but Harold Cohen’s painting machine AARON from 1972 challenged notions of absolute difference between human and machine subjectivity. I showed my first programs about seven years after Harold’s, and like AARON, my programs are rule-based (not machine-learning) generative AIs that assert this same kind of challenge. But your question used the word “tool.” Voyager and AARON aren’t tools, because you can’t tell them what to do. They don’t have “users;” they act like independent creators with their own artistic personalities. This challenges the tool/user discourse that dominates current discussions of musical AI, while obliging us to face the possibility that we aren’t the only creators around.

Question:

What would you say to artists who are hesitant to engage with these tools?

Answer:

I don’t see people being afraid of using AI tools. The real and justified fear is of powerful corporations that are using the tools to replace human musicians. In the 1950s and 1960s, the musicians union tried to ban Hammond organs and synthesizers, but they realized that humans were playing the instruments, so they backed off. But so much music now is encountered via recordings. An AI system can replace session musicians and many listeners won’t care about the difference. And since most MLAI systems just imitate received genres, artists who operate within those genres are at particular risk. But people working outside of those genres have less to fear. And there is still a place for live music, where people empathize with performers. You can’t really empathize with loudspeakers.

Question:

As technology has evolved, what new creative possibilities have opened up for you that weren’t possible when you first began to blend music and computers? How have these shifts expanded, or maybe even challenged, the way you think about making music now?

Answer:

Voyager and its predecessors make musical decisions based on what they hear as well as their own, independent processes. In other words, Voyager can improvise. I don’t see the new AI music tools doing that. That’s not an intrinsic attribute of MLAI; all systems enact the values of the communities the programmers come from. Not everyone wants their machines to improvise — it’s definitely a minoritarian preoccupation.

Most machine learning tech for music depends on imitation, but as someone who comes from Afrodiasporic musical values, I don’t find imitation very attractive; the elders tell you to find your own sound.

In one of my projects at the Institute, I am working with IRCAM researchers on a hybrid program incorporating both rule-based and corpus-based functionality, as a way of moving beyond imitation and toward creativity. As I see it, the only way (for now) for AI to produce new music is to be programmed by people who are themselves interested in producing new music. That’s another way of saying that new music comes from new entities with new ideas, whether machine or human.

Want to hear what it sounds like when a machine improvises?

→ Watch George Lewis’s Voyager program make music

And congratulations to George Lewis, a 2025 Pulitzer Prize finalist in music for his opera composition “The Comet.”

George Lewis is an American composer, musicologist, and trombonist. He is Professor of American Music at Columbia University and Artistic Director of the International Contemporary Ensemble. He is a member of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and the Akademie der Künste Berlin, and a corresponding member of the British Academy. Other honors for George Lewis include the Doris Duke Artist Award, a MacArthur Fellowship, and a Guggenheim Fellowship. Published by Edition Peters, Lewis is widely regarded as a pioneer in the development of AI programs that improvise together with human musicians. Lewis holds honorary doctorates from the University of Edinburgh, Harvard University, the University of Pennsylvania, Oberlin College, the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, New England Conservatory, New College of Florida, Birmingham City University, and Curtis Institute of Music.