Following the snake: What I learned about leadership from Mapuche women

The first recipient of Columbia Global's Santiago Center field research grant on how the experience created "a space for transformation" and taught her about the many connections between a community and its land.

“The house is gone,” read the message on my phone. Four days after I’d left Chile, the home where I’d shared meals around a fireplace with the Garrido family had burned to the ground. When I called them, what I heard wasn’t despair but determination. “We are already rebuilding,” they told me. This persistence is what drew me to the women of the Mapuche community in the first place.

As the first recipient of Columbia Global's Santiago Center field research grant, I spent three months with the Julián Collinao Mapuche community near Villarrica, Chile. The journey to begin my research took me from Santiago through desert regions and finally into the volcanic lake district of southern Chile. Villarrica is a small town built alongside a clear blue lake, with the volcano visible in the distance. Looking around at my new surroundings, I thought, “My neighbors are birds now.” The quiet was a welcome change; I hadn’t realized how much I needed this tranquility after months of doing theoretical research in New York.

Activism was My Birthright

Part of my task was to add a gender lens to the report about Mapuche's territory and land situation, which I later learned how Mapuche women are transforming centuries of oppression into collaborative leadership. Working alongside researchers from Universidad Católica, I conducted hour-long interviews with nine Mapuche families, recording their stories and mapping their territorial claims. Together, we created a 40-page anthropological report that could help the community defend their sacred lands from development. But what began as academic fieldwork quickly became deeply personal.

This journey felt destined. My father spent his career as a federal prosecutor for indigenous rights in Brazil, while my mother fought for workers’ rights. They met during university volunteer work in a project called "Projeto Rondon", setting an example of justice as a daily practice. My grandmother, the first female leader of the Lions Club in her hometown, Tapejara, introduced my mother and then me to spirituality that resonated deeply with Mapuche beliefs about interconnection between worlds.

These influences led me to Columbia University’s Master’s in Human Rights program, where my research, grounded in ecofeminism, examines the disturbing connection between deforestation and gender-based violence in the Amazon — the epicenter of such cruelty and inequality in Brazil.

Leading through Collaboration

The Mapuche community bears the name of Jullian Collinao, their direct ancestor and father of Juan Collinao. Juan was described to me as a “diplomat” who navigated both Mapuche and non-Mapuche worlds, meticulously documenting their territory to preserve their rights. Today, his descendants carry this legacy forward. Ruth Garrido leads the Mapuche Territorial Council of Pucón, while her sister Alejandra works as a lawyer protecting ancestral territories. Their approach to leadership transformed my understanding of power. “For Indigenous women, leadership is not merely a tool and it‘s not about power,” I observed in my report. “It’s a necessity to safeguard what is theirs.”

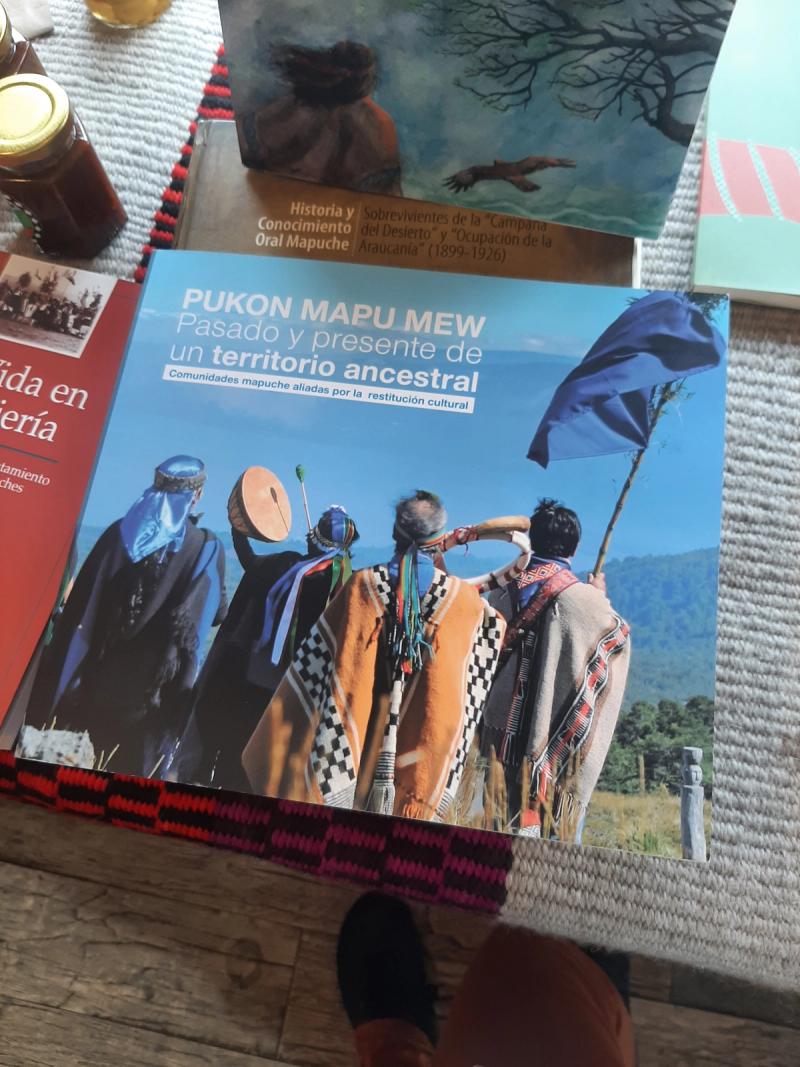

When women lead here, they do so collaboratively. As Alejandra explained, “Power is something shareable.” In a world that often equates leadership with dominance, this perspective feels revolutionary. Their fight to preserve their culture extends beyond land rights — it includes language. The community is actively working to keep their ancestral language, Mapudungún, alive. As part of this effort, their Indigenous association has created a book, Pukon Mapu Mew: Pasado y presente de un territorio ancestral - Comunidades Mapuche Aliadas por la restitución cultural. They are mailing me a physical copy so that their history can travel with me, be shared in foreign lands, and be heard here in New York.

Beyond What We See

When developers look at the hills surrounding Villarrica, they see empty fields for hotels. When the Mapuche look at the same landscape, they see sacred sites marked by specific arrangements of trees, medicinal plants, and burial grounds.

The Villarrica volcano isn’t just a stunning backdrop — they call it “the house of the spirits,” believing that when someone dies, their spirit first goes there to transition to another life. Trees like the Canelo are sacred. Even spiders, which I’ve always feared, are considered protectors of women.

“A tree takes around 100 years to be fully developed — it’s not going to be in two days, and that doesn‘t mean that it’s not productive,” I shared in a Columbia Global webinar I led recently. This understanding of time challenged me profoundly. The Mapuche taught me that just as nature has seasons, so do we. When we don’t respect our own need for rest, we become sick — a lesson that is often ignored in our modern society that values productivity above all else.

Final Days of Celebration

For my farewell, the Mapuche community organized a two-day celebration. The Garrido family cooked feijoada, a traditional Brazilian dish, honoring the connection between our cultures. Polidoro, the family patriarch who had once traveled to southern Brazil, led us in singing Brazilian songs.

One song’s lyrics still move me to tears: “I didn’t learn how to say goodbye, but I had to accept it.” We sang together in the small house they’d been given temporarily after losing their home. Though they had almost nothing, they shared their donations with me, including a pink quartz from their land “for luck.”

We hiked to the Mirador lookout point at León Lagoon, where they explained their struggle to reclaim this sacred water and territory. The paths were altered by outsiders, and we got lost coming down. “Follow the snake,” said one of the community when I spotted one on our path. “It’s a good sign.” Somehow, we found our way.

A Transformation That Remains

Back in New York, I see the world differently. I understand why I feel better in nature — it is alive with spirits we’ve been taught to ignore. I am "not so afraid" of spiders anymore, as through the lens of Mapuche wisdom they are women's allies. I accept my own seasons, knowing that constant production isn’t sustainable.

The Columbia Global Center’s grant provided more than research funding — it created a space for transformation. My experience with the Mapuche women affirmed what I’ve always felt: that environmental destruction and gender oppression are deeply intertwined, and that indigenous wisdom offers solutions our modern systems desperately need.

To the Julián Collinao Mapuche community, especially the Garrido family, I carry your lessons with me. Through our collaborative work and the connections forged by Columbia Global, our paths remain intertwined — just as we all remain connected to the land that sustains us, the ancestral knowledge that guides us, and the collaborative leadership that might yet help us build a more just future.

Watch Vanessa's video about her experience in Villarrica.

Vanessa Fiuza was the first recipient of Columbia Global‘s Santiago Center field research grant, which enabled her three-month study with the Julián Collinao Mapuche community in southern Chile. The Columbia Global Center in Santiago supports graduate students through partnerships with Universidad Católica, providing funding for research at field stations throughout Chile.

For information on how to support the Julián Collinao Mapuche community‘s rebuilding efforts after the fire, please email Damian Garrido Varela at relikura@gmail.com.